Chapter 7 PSYC 2013 Flashcards | Quizlet

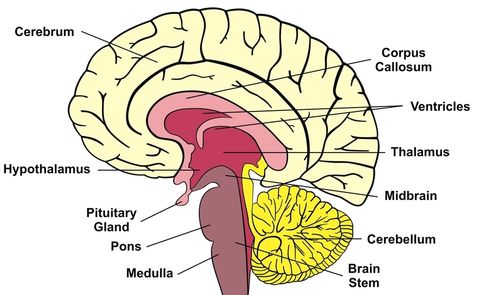

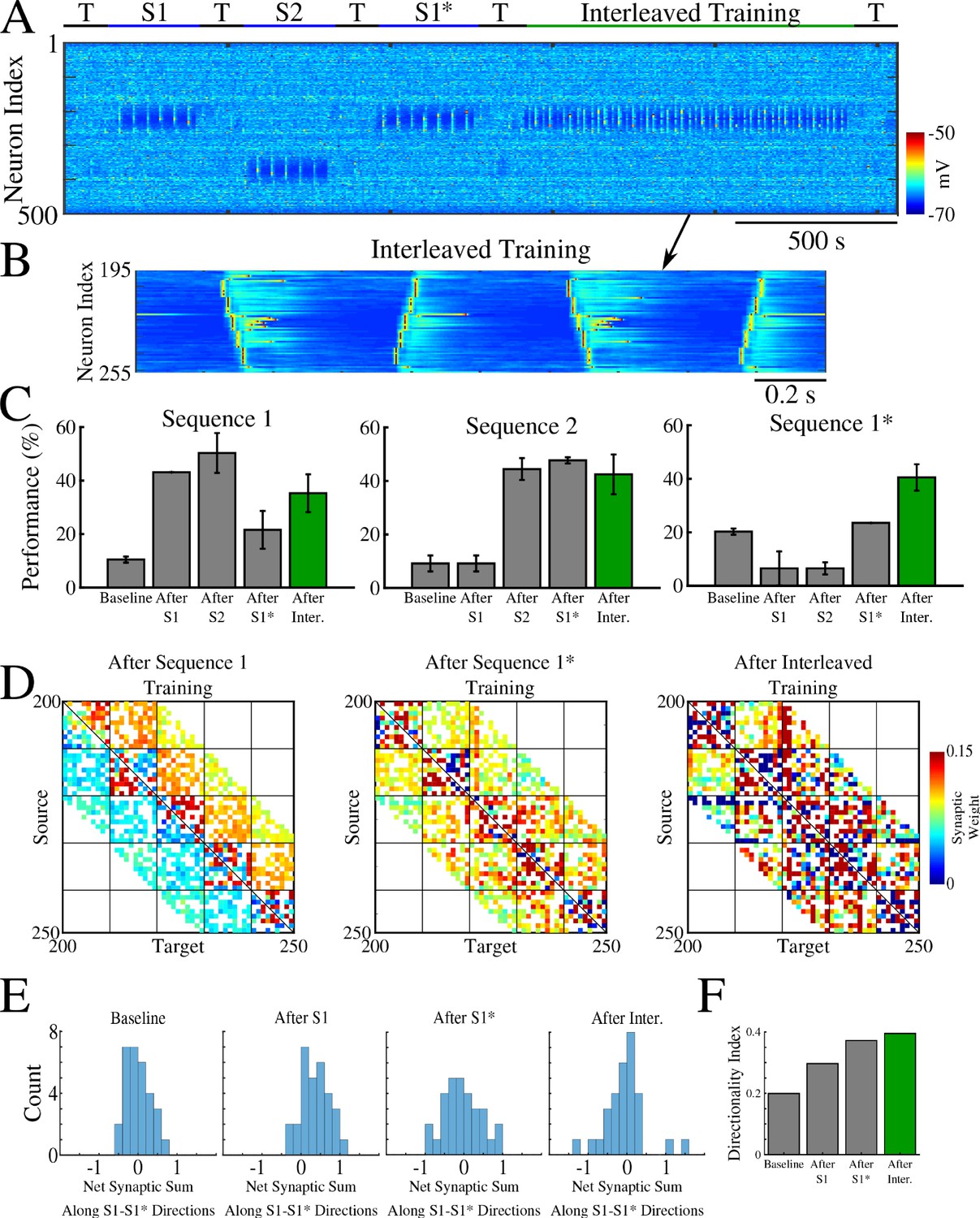

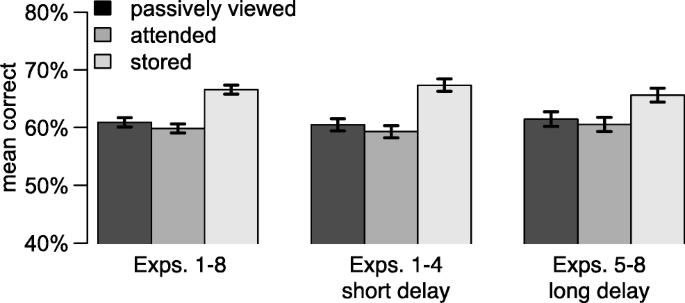

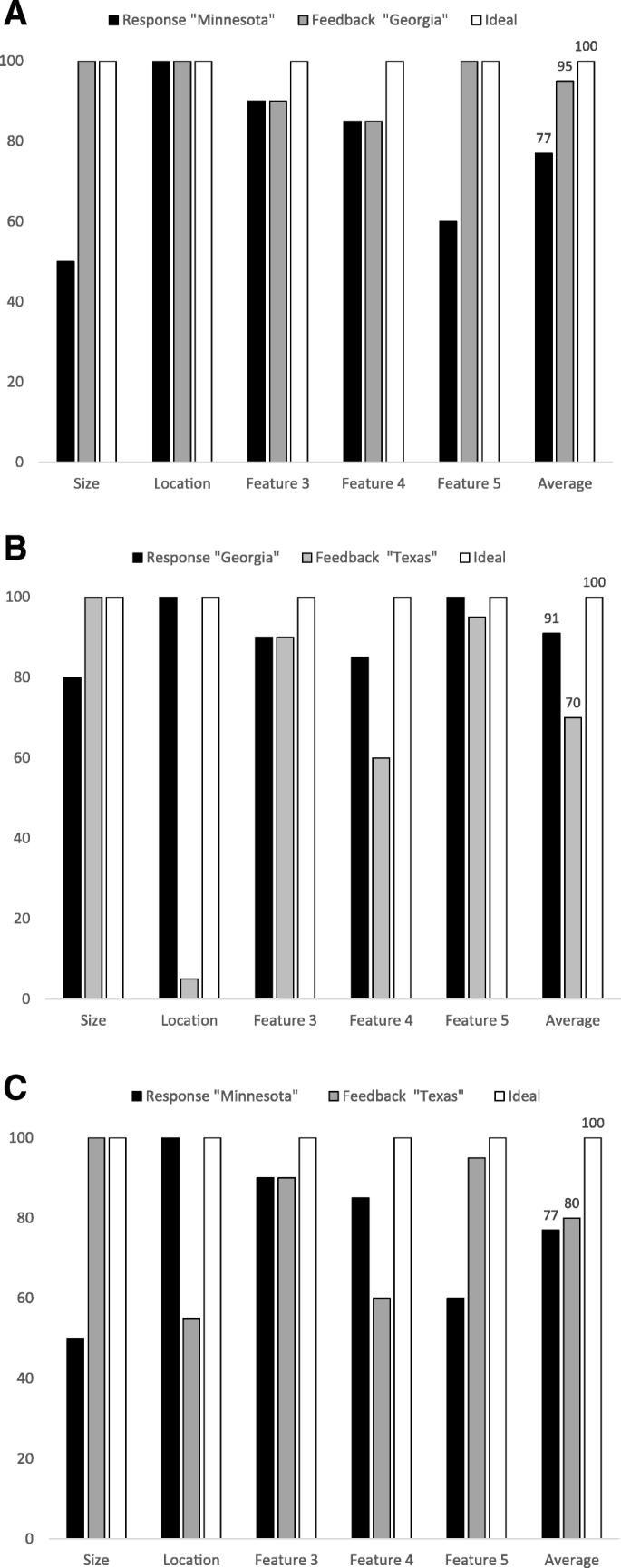

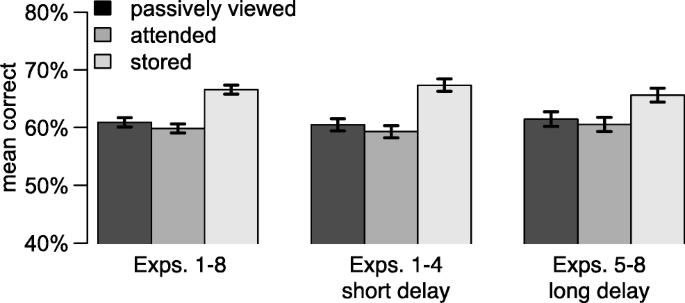

Chapter 7 PSYC 2013 Flashcards | QuizletWarning: The NCBI website requires JavaScript to operate. What are the differences between long-term, short-term memory and working memory? Nelson CowanDepartment of Psychological Sciences, University of Missouri, 18 McAlester Hall, Columbia, MO 65211, USAAbstract In recent literature there has been considerable confusion over the three types of memory: long-term, short-term and work memory. This chapter strives to reduce this confusion and makes up-to-date assessments of these types of memory. Long-term and short-term memory could differ in two fundamental ways, with only short-term memory showing (1) temporary decay and (2) torsion capacity limits. Both short-term memory properties remain controversial, but the current literature is quite encouraging in terms of the existence of decay and capacity limits. The work memory has been conceived and defined in three different forms, slightly discrepant: as short-term memory applied to cognitive tasks, as a multicomponent system that sustains and manipulates information in short-term memory, and as the use of care to manage short-term memory. Regardless of the definition, there are some short-term memory measures that seem routine and do not correlate well with cognitive abilities and other measures (which are usually identified with the term "working agreement") that seem to be more demanding attention and correlate well with these abilities. The evidence is evaluated and placed within a theoretical framework represented in .A representation of the theoretical modeling framework. Modified and refined in later work by , . historical roots of a basic scientific question How many phases of memory are there? In a naive view of memory, you could make a whole cloth. Some people have a good ability to capture facts and events in memory, while others have less skill. However, long before there were real psychological laboratories, a more careful observation must have shown that there are separate aspects of memory. A master of elders could be seen linking the old lessons as vividly as he did, and yet it could be evident that his ability to capture the names of new students, or remember which student made what comment in an ongoing conversation, has decreased over the years. The scientific study of the memory usually goes back to Hermann, who examined his own acquisition and forgetting new information in the form of syllables without sense tested in several periods up to 31 days. Among many important observations, Ebbinghaus noted that he often had a "first leakage capture... of the series at times of special concentration" (p. 33), but that this immediate memory did not ensure that the series had memorized in a way that would allow his memory to be remembered later. Stable memorization sometimes requires new repetitions of the series. Shortly afterwards, he proposed a distinction between primary memory, the small amount of information that remains as the edge of the conscious present and secondary memory, the vast body of knowledge stored throughout life. James's primary memory is like Ebbinghaus's first fleeting capture. The Industrial Revolution made new demands on what the primary memory called. In the 1850s, telegraph operators had to remember and interpret fast series of points and dashes transported acoustically. In 1876 the phone was invented. Three years later, the operators of Lowell, Massachusetts began using phone numbers for more than 200 subscribers so that the substitute operators could be more easily trained if the four regular operators of the city succumbed to a measles epidemic. This use of telephone numbers, complemented by a prefix word, of course disseminated. (The author ' s telephone number in 1957 was Whitehall 2-6742; the number remains assigned, even if it is a seven-digit number.) Even before Ebbinghaus's book, he reported on the serial position curve obtained between the logarithm digits he tried to remember. The senseless syllables that Ebbinghaus had invented as a tool can be seen to have acquired more ecological validity in an industrial era with growing demands for information, perhaps highlighting the practical importance of primary memory in everyday life. The primary memory seems encumbered as it is asked to take into account aspects of an unknown situation, such as names, places, things and ideas that one has not found before. However, the subjective experience of a difference between primary and secondary memory does not automatically guarantee that these types of memory contribute separately to the science of memory. Researchers from a different perspective have long waited for them to write a unique equation, or a unique set of principles, which would capture all memory, from the immediate to the longest. Illustrated that forgetting with time was not simply a question of an inevitable decay of memory but rather of interference during the retention interval; situations in which memory improved, instead of diminishing, with time could be found. From this perspective, you can see what seems to be forgetting about primary memory as the profound effect of the interference of other elements in memory for any element, with interference effects continuing forever, but not totally destroying a given memory. This perspective has been maintained and developed over the years by a constant line of researchers who believe in the unity of memory, including, among others, , , , , , , , , , , , and . Description of three types of memory In this chapter I will evaluate the strength of evidence for three types of memory: long-term memory, short-term memory and work memory. Long-term memory is a vast store of knowledge and record of previous events, and it exists according to all theoretical opinions; it would be difficult to deny that every normal person has a rich, though not impeccable or complete set of long-term memories. Short-term memory is related to primary memory of and is a term that and used in slightly different ways. Like Atkinson and Shiffrin, I take it to reflect the powers of the human mind that may contain a limited amount of information in a very temporarily accessible state. A difference between the term "memory in the short term" and the term "primary memory" is that the latter could be considered more restricted. It is possible that not all ideas temporarily accessible are, or even are, consciously. For example, by this conception, if you are talking to a person with a foreign accent and inadvertently alters your speech to match the accent of the foreign speaker, you are influenced by what was to that point an unconscious (and therefore uncontrollable) aspect of your short-term memory. One could relate short-term memory to a neuronal shooting pattern that represents a particular idea and one could consider the idea of being in short-term memory only when the pattern of shooting, or cell mounting, is active (). The individual may or may not be aware of the idea during that activation period. The work memory is not completely different from short-term memory. It is a term that was used to refer to memory as used to plan and carry out behavior. One is based on the work memory to retain partial results by solving an arithmetic problem without paper, to combine the local in a long rhetorical argument, or to bake a cake without making the unfortunate mistake of adding the same ingredient twice. (His working memory would have been more strongly imposed as I read the previous sentence if I had saved the phrase "one is based on the working memory" until the end of the sentence, which I did within my first draft of that sentence; the working memory thus affects good writing.) The term "working memory" became much more dominant in the field after demonstrating that a single module could not account for any kind of temporary memory. His thinking led to an influential () model in which verbal-phonological and visual-spatial representations were performed separately, and they were managed and manipulated with the help of processes related to care, called the central executive. In the 1974 document, this central executive probably had its own memory that crossed domains of representation. By 1986, this general memory had been removed from the model, but it was added again in the form of an episodic buffer. That seemed necessary to explain the short-term memory of features that did not match the other stores (in particular semantic information in memory) and to explain the cross-domain associations in the work memory, such as the retention of links between names and faces. Because of the work of , the work memory is generally considered as the combination of multiple components working together. Some even include in that package the large contribution of long-term memory, which reduces the workload of working memory by organizing and grouping information in working memory in a smaller number of units (; ). For example, the IRSCIAFBI chart series can be remembered much more easily as a series of acronyms for three federal agencies in the United States of America: the Internal Tax Service (IRS), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). However, that factor was not emphasized in the well-known model of . What is clear from my definition is that the working memory includes short-term memory and other processing mechanisms that help make use of the short-term memory. This definition is different from that used by other researchers (e.g., ), who would like to reserve the term work memory to refer only to aspects related to the attention of the short-term memory. This, however, is not so much a debate on the substance, but rather a slightly confusing discrepancy in the use of terms. One reason to follow the term work memory is that work memory measures have been found to correlate with intellectual abilities (and especially fluid intelligence) better than short-term memory measures and, in fact, possibly better than the measures of any other particular psychological process (e.g., ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). It has been thought that this reflects the use of measures that incorporate not only storage but also processing, being the idea that both storage and processing have to commit simultaneously to evaluate the capacity of work memory in a way related to cognitive aptitude. More recently, he introduced the notion that the skills and working memory depend both on the ability to control care and to apply the control of care to management of primary and secondary memory (). However, more research is needed on exactly what we learn from the high correlation between working memory and intellectual abilities, and this issue will be discussed more after the most basic issue of the short term is addressed in the face of the long-term memory distinction. In the meantime, it may be useful to summarize a theoretical framework (, , , ) based on past research. This framework, illustrated in , helps to take into account the relationship between long-term, short-term and working memory mechanisms and explains what I see as the relationship between them. In this context, short-term memory is derived from a subset of information temporarily activated in long-term memory. This activated subset can be disintegrated as a function of time unless it is refreshed, although the evidence of disintegration remains an attempt at best. A subset of the activated information is the focus of attention, which appears to be limited in torsion capacity (how many separate elements can be included immediately). New partnerships between activated elements can form the focus of attention. The tests related to this modeling framework will now be discussed. The short-term memory/long-term memory distinction If there is a difference between short- and long-term memory stores, there are two possible ways in which these stores can differ: in duration and capacity. A difference of duration means that the elements in the disintegration of short-term storage of this type of storage as a function of time. A difference in capacity means that there is a limit on how many short-term storage items can contain. If there is only one capacity limit, a number of items smaller than the capacity limit could remain in short-term storage until replaced by other items. Both types of limit are controversial. Therefore, in order to assess the utility of the short-term storage concept, the duration and capacity limits will be evaluated in turn. Duration The concept of short-term memory limited by decadence over time was present even at the beginning of cognitive psychology, for example in the work of . If decadence was the only principle that affects performance in an immediate memory experiment, it might be easy to detect this decadence. However, even in Broadbent's work, pollutant variables were recognized. To evaluate decay one must take into account, or overcome, the contaminating effects of the trial, the long-term recovery, and the temporary distinction, which will be discussed one at a time along with evidence for and against decay. Overcoming Rehearsal Pollution According to several researchers there is a process by which you can imagine how the words are pronounced on the list without saying them out loud, a process called an undercover verbal essay. With practice, this process occurs with minimal attention. He used a secondary task to prove that the rehearsal of a list to be remembered was hard on young children, but not in adults. If, in a particular experimental procedure, no short-term memory loss is observed, that pattern of response to the trial can be attributed. Therefore, measures have been taken to eliminate the trial by means of a process called joint deletion, in which a simple pronunciation such as the word "he" is repeatedly pronounced by the participant for part or the whole short-term memory task (e.g., ). There is still a possible objection that any pronunciation used to suppress the trial causes unfortunately interference, which could be the real reason for memory loss over time rather than decadence. That problem of interference would seem mocked in the light of the findings of . They presented lists of letters that should be remembered and varied how long the participant should take to remember each article on the list. In some conditions, they added joint deletion to prevent rehearsal. Despite the deletion, they did not notice any difference in performance over time between the elements in the response that varies between 400 and 1600 ms (or between the conditions in which the word "super" was pronounced one, two or three times among the consecutive articles in the answer). They didn't find evidence of memory decomposition. A limitation of this finding, however, is that the covert verbal test cannot be the only type of test that participants can use. Maybe there are guys who are not prevented by joint deletion. In particular, he suggested that the process of mental assistance to words or search through the list, a process of dismantling attention, could serve to reactivate the elements that will be remembered in a manner similar to the covert verbal essay. The key difference is that joint deletion is not expected to prevent such testing. Instead, to avoid such rehearsal, a care-keeping task should be used., ) have results that seem to suggest that there is another type of rehearsal more attention. They have interposed materials between the articles to remember that they require options; they can be numbers to read out loud or multi-choice reaction times. These are considered to interfere with retention to a degree commensurate with the ratio of the interval between topics used to assist distraction elements. As the speed of distraction elements increases, less items are remembered that are called "rights". The notion is that when the task of distracting does not require attention, liberating attention allows a rehearsal based on the attention of the elements to remember. When the task is more automatic and does not require such attention (e.g., a joint deletion task) there is much less effect of the rate of these elements involved. Based on this logic, one could imagine a version of Lewandowsky's task in which joint deletion is not placed, but the verbal stimuli that give the attention between the elements in the answer, and in which the duration of this time filled among the elements in the answer varies from judgment to judgment. Verbal and care stimuli should prevent both attention-based and articulation-based essay. If there is decay, then performance should decrease in serial positions more severely when longer intervals are placed between the elements in the response. Unfortunately, these results could be considered alternatively as a result of the interference of the stimuli that distract, without the need to invoke decadence. What appears to be necessary, then, is a procedure for preventing joint-based and care-based testing without interference. He tried a kind of procedure that could do it. They presented lists of seven printed digits in which the time between the articles varied within a list. In addition to some random time filling lists, there were four types of critical test, in which the six inter-digit blank intervals were short (0.5 s following each element) or all long (2 s following each element), or they understood three short intervals and then three long, or three long, and then three short intervals. In addition, there were two questions of response after the list. According to a sign, the participant had to remember the list with the articles of the order presented, but at any price he wished. According to the other question of the answer, the list should be remembered using the same time it was presented. The expectation was that the need to remember the time in the last response condition would avoid rehearsal of any kind. As a result, performance must be undermined in trials where the first three response intervals are long because, in these trials, there is more time to forget most of the elements on the list. As predicted, there was a significant interaction between the response signal and the length of the first half of the response intervals. When the participants were free to remember the elements at their own pace, the performance was not better with a short first half (M=.71) than with a long first half (M=.74). The slight benefit of a long first half in that situation could occur because it allowed the list to be tested soon in the response. Instead, when the time of memory had to coincide with the schedule of the presentation of the list, the performance was better with a first short half (M = .70) than with a long first half (M = .67). This, then, suggests that there could be short-term memory decay. Overcoming pollution caused by long-term recovery If there is more than one type of memory storage, then there is still the problem of which store provided the underlying information an answer. There is no guarantee that only because a procedure is considered a short-term storage test, the long-term store will not be used. For example, in a simple task of the lapse of digits, a series of digits is presented and will be repeated immediately after memory. If that series turned out to be only slightly different from the participant's phone number, the participant could memorize the new number quickly and repeat it over the long term. Double store memory theories allow this. Although and drawn their information processing models as a series of boxes that represent different memory stores, with long-term memory after short-term memory, these boxes do not imply that the memory is exclusively in one box or another; they are best interpreted as the relative times of the first stimulus in one store and then the next. The question remains, then as to how one can determine whether a response comes from short-term memory. It developed a mathematical model to achieve this. The model operated with the assumption that long-term memory is produced for the entire list, including a plateau at the center of the list. On the other hand, at the time of recall, it is said that short-term memory only remains at the end of the list. This model assumes that, for any particular serial position within a list, the probability of successful short-term storage (S) and long-term storage (L) are independent, so the probability of remembering the article is S+L−SL. A slightly different assumption is that short- and long-term stores are not independent, but are used in a complementary manner. The availability of short-term memory of a topic may allow the resources necessary for long-term memorization to be moved to other locations on the list. Data seem more consistent with that assumption. In several studies, lists have been submitted to patients with Korsakoff amnesia and normal control participants (; ). These studies show that, in immediate memory, the performance in amnionic individuals is preserved in the latest serial positions on the list. It is as if the performance in these serial positions is based mostly or entirely on short-term storage, and that there is no decrease in that kind of storage in the amnestic patients. In the delayed memory, the amnestic patients show a deficit in all serial positions, as it would be expected that the short-term memory for the end of the list will be lost as a function of a full delay period (). Overcoming Pollution by Temporary Distinction Finally, it has been argued that waste of memory with time is not necessarily the result of decadence. On the other hand, it can be caused by temporary distinctiveness in recovery. This kind of theory assumes that the temporary context of an article serves as a test of recovery for that article, even in free memory. A separate item in the time of all other articles is relatively distinctive and easy to remember, while an article that is relatively close to other articles is more difficult to remember because it shares its temporary files to recovery. Shortly after presenting a list, the most recent elements are the most temporarily different (such as the difference of a phone pole that is practically playing compared to the poles that extend down the road). Through a retention interval, the relative distinctiveness of the most recent elements decreases (such as being away even from the last pole of a series). Although there are data that can be interpreted according to distinctiveness, there are also what seem to be dissociations between the effects of distinctiveness and a genuine short-term memory effect. You can see this, for example, in the classic procedure in which the trigrams of letters should be remembered immediately or only after a distracted task, counting back from a start number by three, for a period of up to 18 s. Peterson and Peterson found a severe memory loss for the trigram of letters as the full delay increased. However, later, skeptics argued that memory loss occurred because the temporal distinctiveness of the current trigram of cards decreased as the total delay increased. In particular, it was said that this effect of delay occurred due to the increased delays in testing in proactive interference with previous trials. In the first few trials, the delay does not matter () and there is no adverse effect of the delay if the delays of 5, 10, 15 and 20 s are tested in separate test blocks (; ).However, there may be a real decay effect in shorter test intervals. configure a trailer in a shopping center so that they can test a large number of participants for a test each, in order to avoid proactive interference. They found an effect of the test delay within the first 5 s but not longer delays. However, it seems that the concept of decay is not yet on very firm ground and guarantees a deeper study. It may be that decadence actually reflects not a gradual degradation of the quality of the short-term memory trail, but a sudden collapse at a point that varies from judgment to judgment. With the control of the temporal distinctiveness, what could be a sudden collapse in the representation of memory for a tone with delays of between 5 and 10 s.Cunk capacity limits The concept of capacity limits was raised several times in the history of cognitive psychology. famously discussed the "magic number seven more or less two" as a constant in short-term processing, including list memory, absolute judgment, and numerical estimation experiments. However, its autobiographical essay () indicates that it was never very serious about number seven; it was a rhetorical device that used to tie together the threads of its non-related research in another way for a chat. Although it is true that memory lapse is approximately seven items in adults, there is no guarantee that each item is a separate entity. Perhaps the most important point in the article was that several elements can be combined into a larger and meaningful unit. Further studies suggested that the capacity limit is more typically only three or four units (; ). This conclusion was based on an attempt to take into account strategies that often increase the efficiency of the use of a limited capacity, or allow for additional information separate from that limited capacity. To understand these methods of discussing capacity limits, I will again mention three types of pollution. These come from tugs and the use of long-term memory, rehearsal and non-capacity-limited storage types. Overcoming the contamination of the whirlpool and the use of long-term memory The response of a participant in an immediate memory task depends on how the information to be remembered is grouped to form fragments of various topics (). Because it is generally not clear which pieces have been used in memory, it is unclear how many pieces can be retained and if the number is really fixed. He proposed some situations in which the formation of several topics was not a factor, and suggested on the basis of the results of such procedures that the true capacity limit is three elements (each of which serves as a single point). For example, although the memory interval is usually about seven elements, errors are made with lists of seven points and the error-free limit is usually three elements. When people must remember items in a long-term memory category, such as the states of the United States, they do so in spurts of approximately three articles on average. It is as if the cube of short-term memory is filled with the long-term memory well and must be emptied before it is filled. He pointed out other such situations in which fragments of several points cannot be formed. For example, in the period of execution memory, a long list of articles is presented with an unpredictable endpoint, making the group impossible. When the list ends, the participant must remember a certain number of items from the end of the list. Typically, people can remember three or four elements from the end of the list, although the exact number depends on the task demands (). People differ in capacity, ranging from two to six articles in adults (and less in children), and the individual capacity limit is a strong cognitive aptitude correlation. Another way to take into account the role of the formation of several points is to establish the task in a way that allows to observe the pieces. He studied the free remembrance of the lists of words with various levels of structure, ranging from random words to well-formed phrases in English, with several different levels of coherence between. A piece is defined as a series of words reproduced by the participant in the same order in which the words were presented. It was estimated that, under all conditions, participants remembered an average of four to six pieces. He tried to perfect that method by testing the eight-word lists in series memory, which consists of four pairs of words that had previously been associated with several learning levels (0, 1, 2, or 4 pairs of previous words). Each word used in the list was presented an equal number of times (four, except in an unstudyed control condition) but the varied was how many of those presentations were as singletons and how many were like a consistent pairing. The number of paired pre-expositions remained constant through the four pairs on a list. A mathematical model was used to estimate the proportion of remembered pairs that could be attributed to the learned association (i.e., a piece of two words) rather than to separately remember the two words in a pair. This model suggested that the capacity limit was about 3.5 pieces in each learning condition, but that the ratio of two-word to piece pieces of a word increased as a function of the number of pre-event exposures on the list. Overcoming Rehearsal Pollution The subject of rehearsal is not completely separated from the topic of forming pieces. In the traditional concept of rehearsal (e.g., ), it is imagined that the elements are articulated in covert form in the order presented at a uniform rate. However, another possibility is that the trial involves the use of joint processes to put the elements into groups. In fact, he asked participants in a period of digits how they carried out the task and far the most common answer among adults was that they grouped the articles; the participants rarely mentioned saying the articles themselves. However, it is clear that the deletion of the trial affects performance. Presumably, situations in which the articles cannot be tested are mostly equal to situations in which the articles cannot be grouped. For example, it was based on a functioning memory duration procedure in which the articles were presented at speed of 4 per second. At that rate, it is impossible to test the elements as presented. On the other hand, the task is likely to be done by keeping a passive store (sensory or phenological memory) and then transferring the latest items from that store to a store more related to attention at the time of remembering. In fact, with a rapid presentation rate in the performance period, the instructions for testing the elements are harmful, not useful, for performance (). Another example is the memory of the lists that were ignored at the time of their presentation (). In these cases, the capacity limit is close to the three or four topics suggested by and . It is still quite possible that there is a short-term storage mechanism based on speech that is by a comprehensive and independent mechanism of the torbelline-based mechanism. In terms of the popular model of , the first is the phonological loop and the last, the episodic buffer. In terms of , , , , the first is part of the activated memory, which can have a time limit due to the decadence, and the last is the focus of attention, which is supposed to have a limit of torsion capacity. showed that the time limit and the limit of sinking capacity in the short-term memory are separated. They repeated the procedure in which sometimes pairs of words were presented at a pre-memorial training session of the list. They combine composite lists of pairs as in that study. Now, however, free and serial memory tasks were used, and the length of the list was varied. For long lists and free memory, the capacity limit of the cake governed the memory. For example, lists of six well-learned pairs, as well as lists of six unpaid singletons (i.e., were remembered in similar proportions of correct words). For shorter lists and strictly scored serial memory, the time limit ruled the memory. For example, the well-learned four pair lists were not remembered almost as well as the unpaid four singleton lists, but only as well as the lists of eight unpaid singletons. For the intermediate conditions it seemed as if the limits of capacity and the operating periods of set to govern the memory. Perhaps the mechanism limited by capacity contains elements and the test mechanism retains a certain serial order memory for those items maintained. The exact way these limits work together is not yet clear. Overcoming pollution from unlimited storage types It is difficult to demonstrate a true limit of attention-related capacity if, as I think, there are other types of short-term memory mechanisms that complicate the results. A general capacity should include fragments of information of all types: for example, information derived from acoustic and visual stimuli, as well as verbal and non-verbal stimuli. If this is the case, there must be cross interference between one type of memory load and another. However, literature has often shown that there is much more interference between similar types of memoranda, such as two visual arrays of objects or two lists of words presented acoustically, that there are between two different types, such as a visual matrix and a verbal list. He suggested that there is little or no interference between the desimilar lists. If so, that would seem to provide an argument against the presence of a warehouse of general memory, of cross-domain and in the short term, questioning this conclusion. They presented a visual array of color stains to compare with a second array that matched the first or differs from it in the color of a single point. Before the first matrix or right after it, the participants sometimes heard a list of digits that were then recited between the two arrays. In a low load condition, the list was its own seven-digit phone number, while, in a high load condition, it was a random number of seven digits. Only this last condition interfered with the performance of the array comparison, and then only if the list was recited loudly among the arrays. This suggests that the recovery of seven random digits in a way that also involves test processes depends on some kind of short-term memory mechanism that is also necessary for visual arrays. This shared mechanism can be the focus, with its capacity limit. Apparently, although, if the list remained silently instead of being recited aloud, this silent maintenance occurred without much use of the common storage mechanism based on attention, so the performance of the visual matrix was not very affected. Short-term memory types whose contribution to memory may obscure the capacity limit may include any type of activated memory that fall out of the focus. In the modeling frame represented in , this may include sensory memory features as well as semantic features. Famous illustrates the difference between unlimited sensory memory and limited classed memory of capacity. If a set of characters was followed by a partial report soon after the matrix, most characters in the string row can be remembered. If the cue was delayed about 1 s, most sensory information had decayed and performance was limited to about four characters, regardless of the size of the array. Based on this study, the four-character limit could be considered as a limit in short-term memory capacity or a limit in the rate with which the information could be transferred from the sensory memory to a categorical form before it was disintegrated. However, he carried out an auditory analog experiment and found a limit of approximately four elements, although the observed disintegration period for the sensory memory was about 4s. In view of the surprising differences between Sperling and Darwin and others in the period available for the transfer of information to a categorical form, the common limit of four topics is considered better as a capacity limit rather than a tariff limit. He tested this conceptual framework in a series of experiments in which arrays were presented in two modes at a time or, in another procedure, one after another. A visual range of color stains was complemented by a series of spoken digits that occur in four separate speakers, each consistently assigned to a different voice to facilitate perception. In some trials, participants knew they were responsible for both modalities at the same time, while in other trials participants knew they were solely responsible for visual or acoustic stimuli. They received a probe matrix that was the same as the previous matrix (or the same modality as one in that previous matrix) or differ from the previous array in the identity of an stimulus. The task was to determine whether there was a change. The use of the cross-sectional mode, storage limited by capacity predicts a particular pattern of results. You will predict that performance in any of the modalities should be reduced in the duality condition compared to the unimodale conditions, due to the strain in the cross-modality store. That's how it was. On the other hand, if the multimodal store, of limited capacity was the only type of storage used, then the sum of the visual and auditory abilities in the condition of duality should not be greater than the greater of the two unimodale abilities (which happened to be the visual capacity). The reason is that the limited capacity store would have the same number of units no matter whether they were all one modality or two combined modalities. That prediction was confirmed, but only if there was a post-perceptual mask in both modalities immediately after the matrix that will be remembered. The post-perceptual mask included a multicolour point in each location of the visual object and a sound composed of all possible oversolute digits of each speaker. It was presented enough after the arrays were remembered that their perception would have been complete (e.g., 1 s later; cf. ). Presumably, the mask was able to overwrite various types of sensory characteristics specific to the activated memory, leaving behind only the most generic and categorical information present in the focus of attention, which is presumably protected against interference in the care process. The attention limit was again shown between three and four elements, either for visual or bimodal unimodale stimuli. Even without using masking stimuli, it may be possible to find a phase of the short-term memory process that is general through the domains. presented two stimulus sets that will be remembered (or, in control conditions, only one set). The two stimulus sets could include two spoken lists of digits, two spatial arrays of color stains, or one of each, in any order. After this presentation, a cue indicated that the participant would be responsible for only the first array, only the second array, or both arrays. Three seconds in a row before a probe. The effect of the memory load could be compared in two ways. The results in the trials in which two stimulus sets were presented and both were taken care of for retention were compared to the trials in which only one set was presented, or could be compared to the trials in which both sets were presented but the point below indicated that only one set had to be maintained. The part of the pre-quae work memory showed specific dual-tasking effects for the modality: the encoding of a stimulus set of one type was further injured by encoding another set if both sets were in the same modality. However, the retention of information after the signal showed dual tension effects that were not specific to the modality. When two sets had been presented, retaining both was detrimental compared to retaining only one set (as specified in the post-stimulus retention box to retain one against both sets), and this dual-voltage effect was similar in magnitude regardless of whether the sets were in the same or different modalities. After the initial encoding, the storage of work memory in several seconds can occur abstractly, in the focus of attention. Other tests for short-term separate storage Finally, there are other tests that do not directly support temporary decay or a capacity limit specifically, but it implies that one or the other of these limits exist. and made temporary distinctive arguments on the basis of what is called "continuous recordance of the list of distractors", in which there persists a right effect even when the list is followed by a delay filled with distractions before recalling. The total delay must have destroyed the short-term memory, but the recreation effect occurs anyway, provided that the elements of the list are also separated by delays filled with distractors to increase their distinction between them. In favor of short-term storage, however, other studies have shown dissociations between what is in the ordinary immediate memory against the continuous memory of the distractor (e.g., effects of word length reversed in continuous distracting memory: ; proactive interference in the most recent list positions in continuous distractor remember only: ; ). There is also additional neuroimaging evidence for short-term storage. found that the recognition of previous portions of a list, but not of the latest elements, activates areas within the hypocampal system that is usually associated with long-term memory recovery. This is consistent with the finding, mentioned above, that the memory of the last few items on the list is saved in the amnesia of Korsakoff (; ). In these studies, the portion of the short-term memory-based recreation effect could reflect a short amount of time between the presentation and the memory of the latest topics, or could reflect the absence of interference between the presentation and the memory of the latest topics. Therefore, we can say that short-term memory exists, but often without much clarity as to whether the limit is a time limit or a limit of torsion capacity. The distinction of short-term memory/working memory The distinction between short-term memory and working memory is clouded in some confusion, but it is largely the result of different researchers using different definitions. He used the term "working memory" to refer to temporary memory from a functional point of view, so from his point of view there is no clear distinction between short-term memory and working memory. They were quite consistent with this definition, but it exceeded some descriptions in the terms that distinguish them. They thought of short-term memory as the unit retention site described by, for example, . When they realized that the evidence was actually consistent with a multicomponent system that could not be reduced to a short-term unit store, they used the term work memory to describe the whole system. It maintained a multicomponent vision, such as Baddeley and Hitch, but without a commitment to precisely its components; instead, the basic subdivisions of the work memory were said to be the short-term storage components (memory activated along with the focus within it, shown in ) and the central executive processes that manipulate the stored information. For Cowan's sake, the photological loop and the visuospatial sketch would look like only two of many aspects of the activated memory, which are susceptible to interference to a degree that depends on the similarity between the characteristics of the activated and interfered sources of information. The episodic damper is possibly the same as the information stored in the Cowan focus, or at least it is a very similar concept. There has been some change in the definition or description of the work memory along with a change in the explanation of why new work memory tasks correlate with the intelligence and fitness measures much higher than doing simple, traditional and short-term memory tasks, such as serial memory. I had assumed that what is critical is to use work memory tasks that include storage and processing components, to involve all parts of the work memory as described, for example, by . Instead, and proposed that what is critical is whether the work memory task is challenging in terms of care control. For example, Kane et al. found that the tasks of storage and processing of work memory correlate well with the ability to inhibit the natural tendency to look towards a sudden stimulus that appears and instead of looking to the other side, the antisaccade task. Similarly, it was found that individuals who write down the storage and processing tests of the work memory notice their names on a channel to be ignored in dicotic listening much less often than low-level individuals; high-level individuals are apparently more able to do their primary task performance less vulnerable to distraction, but this comes at the expense of being somewhat oblivious to irrelevant aspects of their environment. In response to this research, Engle and her colleagues sometimes used the term work memory to refer only to processes related to care control. In doing so, its definition of work memory seems to disagree with previous definitions, but that new definition allows the simple assertion that the working memory correlates very with abilities, while the short-term memory (redefined to include only the non-related aspects of memory storage intent) does not correlate so highly with abilities., while adhering to the more traditional definition of work memory, made an affirmation about the little more complex work memory. They proposed, on the basis of some development and correlation evidence, that multiple care functions are relevant to individual differences in skills. Attention control is relevant, but there is an independent contribution to the number of issues that may be considered or their scope. According to this view, what may be necessary for a working memory procedure to correlate well with cognitive abilities is that the task should prevent the undercover verbal rehearsal so that the participant should rely on greater processing and/or storage to carry out the task. found that the task can be much simpler than the storage and processing procedures. For example, in a version of the memory duration test, the digits are presented very quickly and the series stops at an unpredictable point, after which the participant must remember as many items as possible from the end of the list. The test is impossible and, when the list ends, the information must allegedly be recovered from sensory or phenological features activated in the focus. This type of task was correlated with skills, as did other measures of the scope of care (, ). In children too young to use the covert verbal test (unlike older children and adults), even a simple task of the digit lapse served as an excellent correlate with abilities. Other researches verify this idea that a work memory test will correlate well with cognitive abilities to the extent that it requires attention to be used for storage and/or processing. carried out a development study in which they controlled the difficulty and duration of a processing task that arose between the articles to remember. There is still a development difference in the field, which attributes to the development of a basic capacity, which could reflect an increase in the scope of development care (cf. ). showed that what was important for a type of storage and processing task to correlate well with abilities is that the task processing component (in this case, reading letters in the loud) occurs fast enough to prevent several types of testing from entering between (see also the processing of the data). it used a modified visual matrix task for use with a component of event-related potentials that indicates storage in visual work memory, called contralateral delay activity (CDA). This activity was found to depend not only on the number of relevant objects on the screen (e.g. red bars in different angles to remember), but also sometimes on the number of irrelevant objects to be ignored (e.g. blue bars). For high-end individuals, it was found that the CDA for two relevant objects was similar if there were also two irrelevant objects on the screen. However, for low-level individuals, the CDA for two relevant objects combined with two irrelevant objects was similar to the CDA for displays with four relevant objects alone, as if the irrelevant objects could not be excluded from the working memory. One limitation of the study is that the separation of participants in the high or low period was based on the CDA as well, and the task used to measure the CDA inevitably required selective attention (half of the screen) in each trial, whether it included objects of an irrelevant color. investigated similar problems in behavioral design, and tested the difference between schizophrenic patients and normal control participants. Each trial started with a signal to assist one part of the screen at the expense of another (e.g., bars of a relevant color but not another irrelevant color). The probe screen was a set that was taken care of for the relevance in most trials (in some experiments, 75%) while occasionally the probe screen was a set that was not taken care of. This allowed for a separate measure of attention control (the advantage of the elements marked on the unobserved elements) and the storage capacity of the work memory (the average number of elements remembered from each matrix, adding whole and unfulfilled assemblies). Unlike the initial expectations, the clear result was that the difference between groups was in capacity, not in the control of attention. It would be interesting to know whether the same type of result could be obtained for ordinary high or low-level people, or whether that comparison would instead show a difference in the control of participation among these groups as it should predict. It found that not all central executive functions were related to skills; the updating of the working memory did, but inhibition and change of care did not. On the other hand, remembering that it was found that a task of monitoring assistance was related to skills. In short, the question of whether short-term memory and working memory are different can be a matter of semantics. There are clearly differences between simple serial memory tasks that do not correlate very well with adult fitness tests, and other tasks that require memory and processing, or memory without trial possibility, that correlate much better with abilities. Whether to use the term work memory for this last set of tasks, or to reserve that term for the whole system of preservation and manipulation of short-term memory, it is a matter of taste. The most important and substantive issue may be why some tasks are more appropriately correlated than others. Conclusion The distinction between long-term and short-term memory depends on whether there are specific short-term memory properties; the main candidates include temporary decay and a limit of torsion capacity. The issue of disintegration remains quite open to debate, while there is growing support for a capacity limit. These limits were discussed in a frame shown in . The distinction between short-term memory and work memory is one that depends on the definition that one accepts. However, the substantive issue is why some short-term memory tests serve as some of the best correlations of cognitive abilities, while others do not. The response seems to indicate the importance of a care system used both for processing and storage. The efficiency of this system and its use in the work memory seem to differ substantially to individuals (e.g., ; , ), as well as to improve development in childhood (, ) and decrease in old age (; ; ). Recognition This work was completed with the assistance of NIH Grant R01 HD-21338. ReferencesFormats: Share , 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, 20894 USA

Accessibility links Search results Web results Chapter 7 Inquizitive Flashcards _ QuizletChapter 7 PSYC 2013 Flashcards The Voting in English Quizlet Web Results Inquizitive Ch. 7 Memory formation How can the cutter help to work the memory? - Pub MedChunking (psychology) - Wikipedia How the Chunking technique can help improve your MemoryStep 1: Memory coding How does Chunking help the work memory? tense Request PDFPractice Quiz9.1 Memories like Types and Stages – Introduction to both psychology recalling searchesidentify formation coincides with each process of name with a review. matchprinciples with their corresponding examples. Long-term identification can be distorted. combine each contipinform brain area that processes or stores. corresponds to each term with its corresponding process. corresponds to each typefailure with its corresponding example. Schemes help a person codify and retrieve information? Navigation page1 Foot links

Chapter 7 PSYC 2013 Flashcards | Quizlet

Chapter 7 PSYC 2013 Flashcards | Quizlet

Chapter 7 PSYC 2013 Flashcards | Quizlet

Chapter 7 PSYC 2013 Flashcards | Quizlet

Chapter 7 notes.docx - Mark is listening to a song attention through one earbud He auditory attention repeats the lyrics to himself as he tries to learn | Course Hero

Age-Related Memory Loss - HelpGuide.org/confabulation-definition-examples-and-treatments-4177450_FINAL-c1dd037aeb66402a9d44c5c2490467b5.png)

Confabulation: Definition, Examples, and Treatments

Memory, Forgetfulness, and Aging: What's Normal and What's Not? | National Institute on Aging

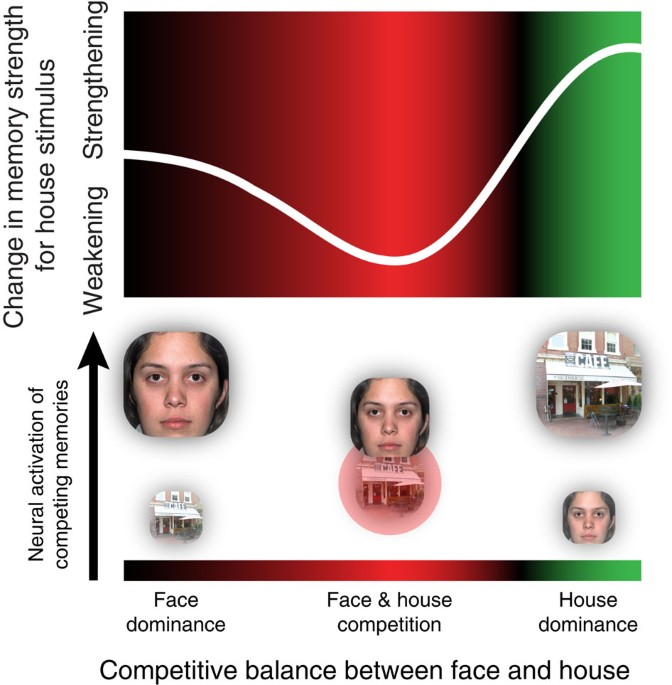

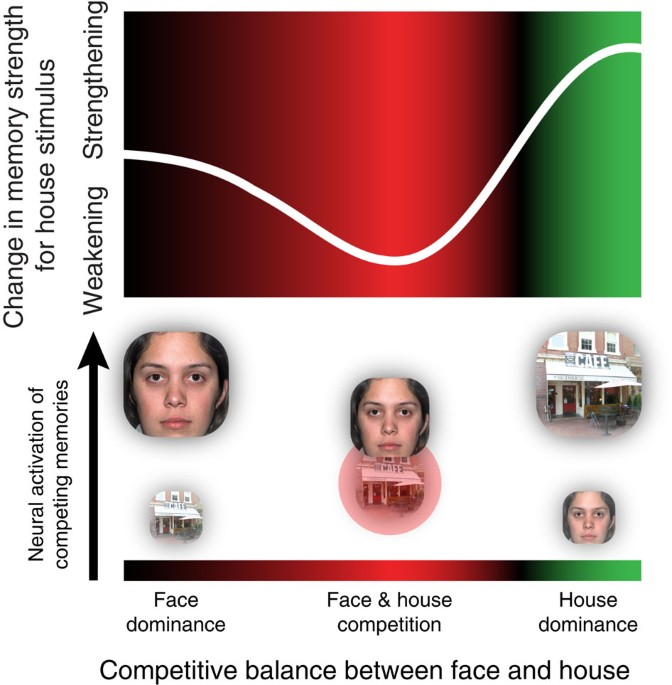

Competition between items in working memory leads to forgetting | Nature Communications

Do Memory Problems Always Mean Alzheimer's Disease? | National Institute on Aging

Short-Term Memory Loss: Definition, Causes & Tests | Live Science

10 signs and symptoms of early-onset Alzheimer's

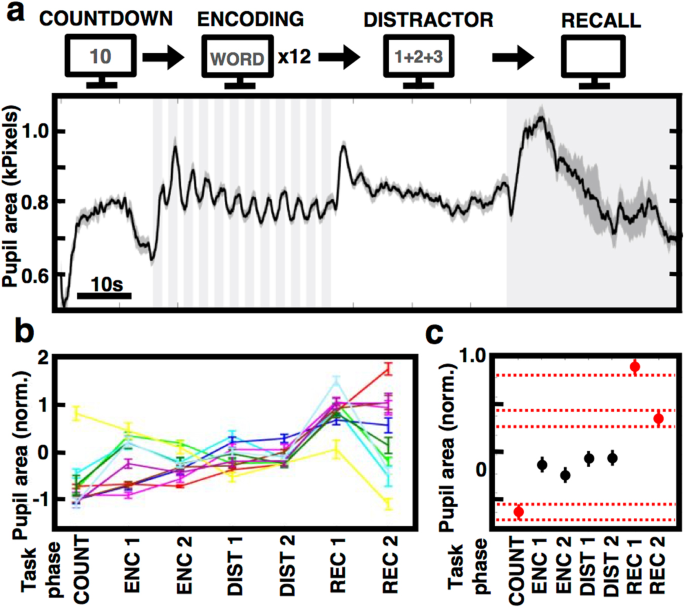

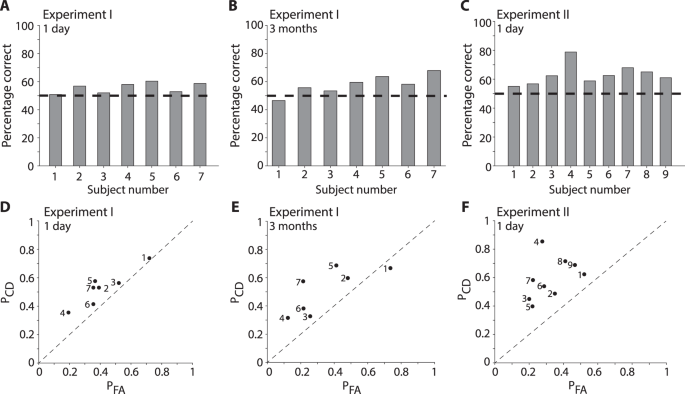

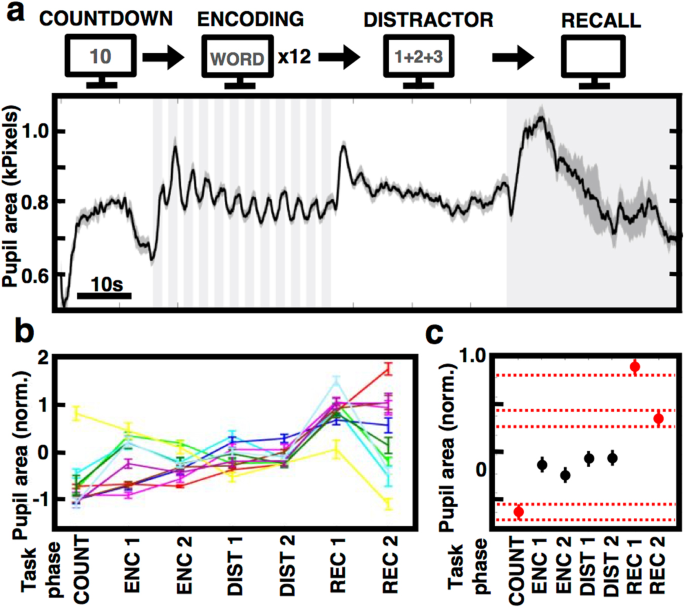

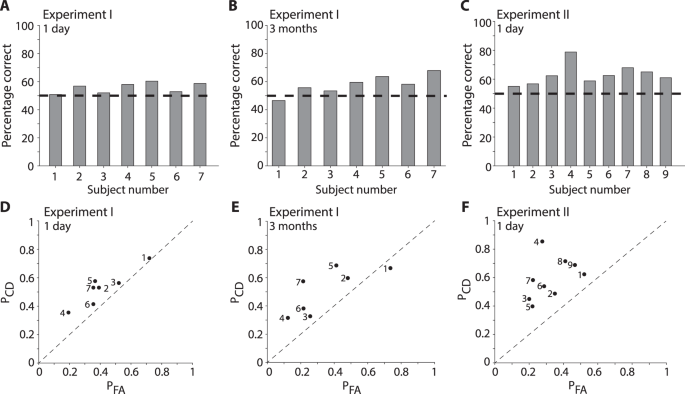

Pupil size reflects successful encoding and recall of memory in humans | Scientific Reports

Minimal memory for details in real life events | Scientific Reports:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-592016219-58b0a7403df78cdcd8da56e6.jpg)

Memory Loss Causes: Alzheimer's, Depression, and More

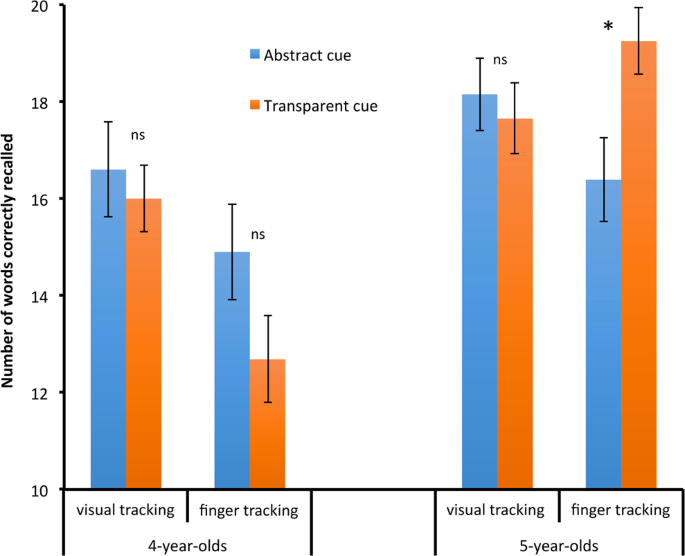

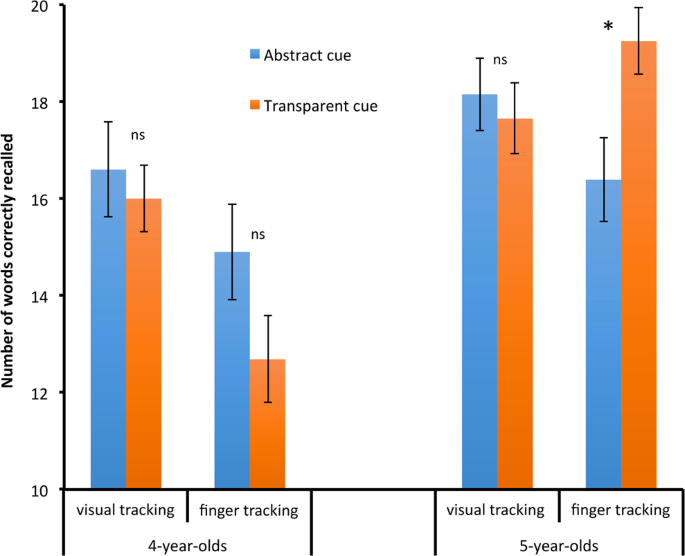

Five-Year-Old Children's Working Memory Can Be Improved When Children Act On A Transparent Goal Cue | Scientific Reports

Short Term Memory Loss: What Every Family Needs to Know

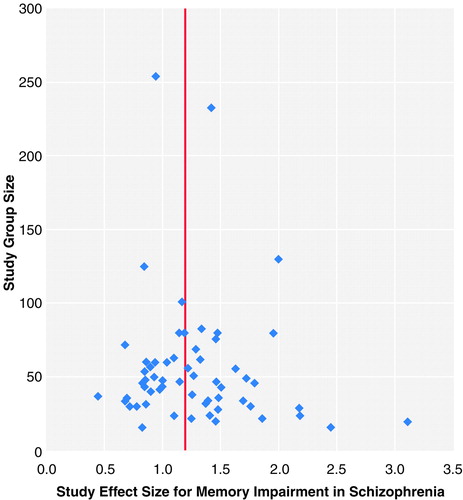

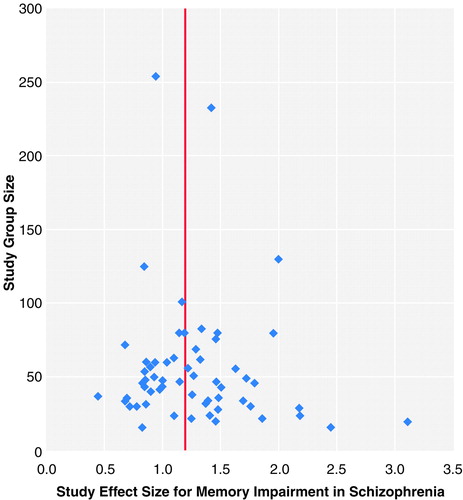

Memory Impairment in Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis | American Journal of Psychiatry

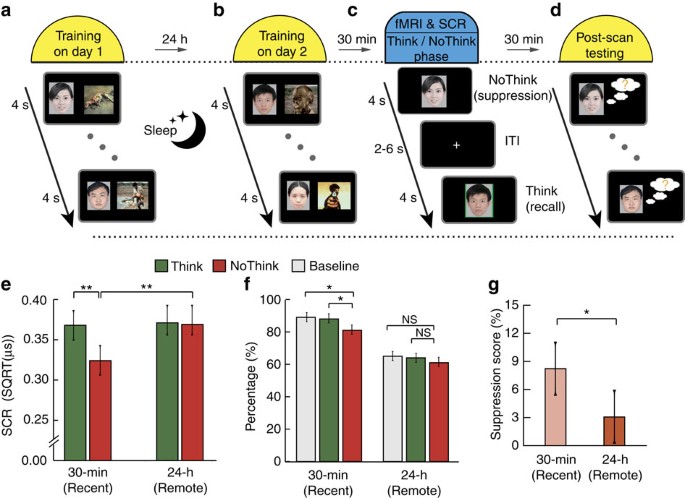

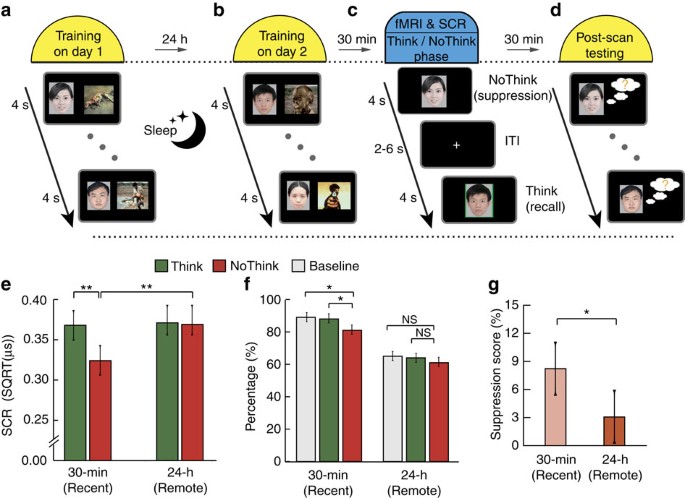

Memory consolidation reconfigures neural pathways involved in the suppression of emotional memories | Nature Communications

7 ways to keep your memory sharp at any age - Harvard Health/do-thyroid-disorders-cause-forgetfulness-98837_V3-362c2781bfe746eb8d438a1559fe8eb9.jpg)

Do Thyroid Disorders Cause Forgetfulness and Brain Fog?

Decay happens: the role of active forgetting in memory

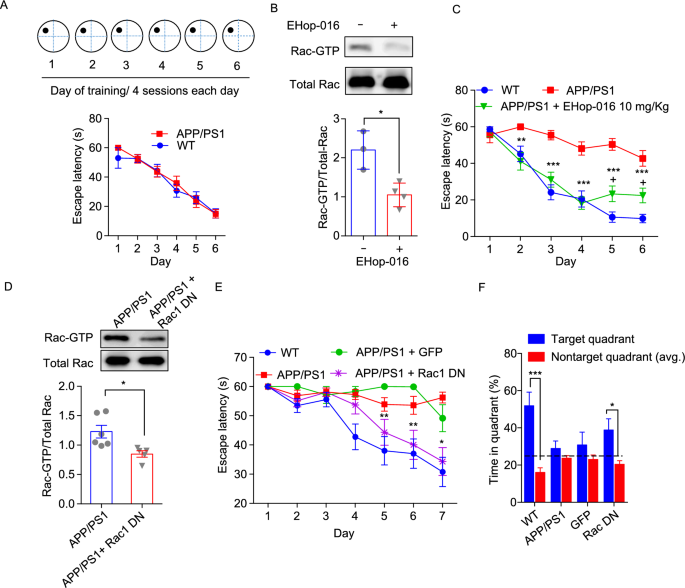

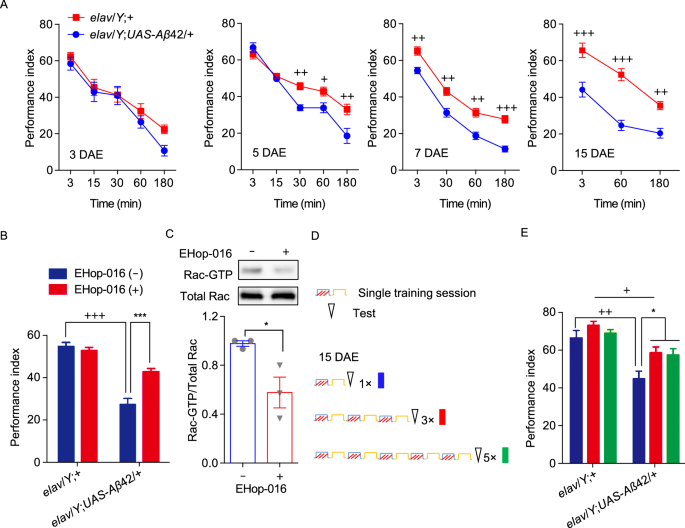

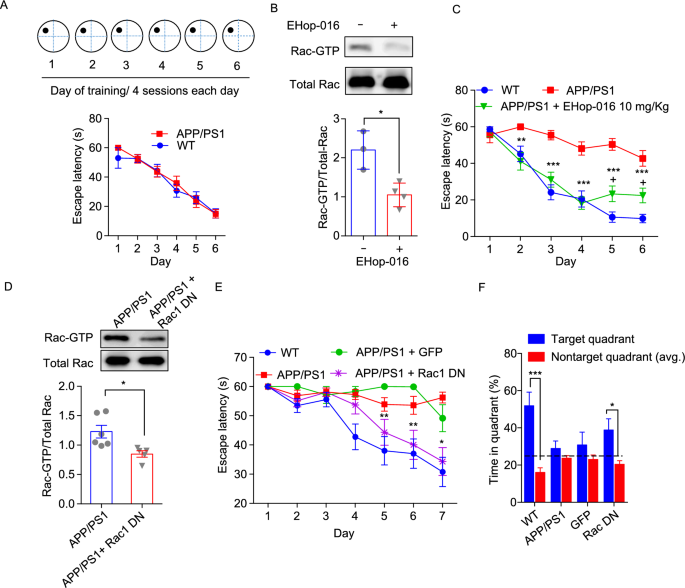

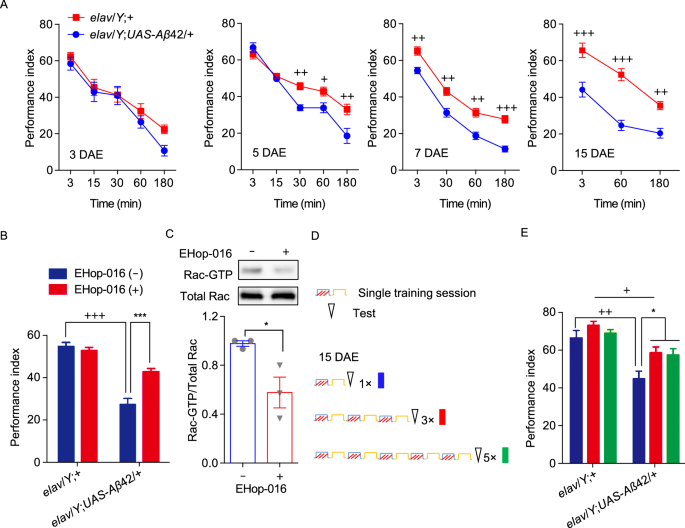

Inhibition of Rac1-dependent forgetting alleviates memory deficits in animal models of Alzheimer's disease | SpringerLink

Forgetting but not gone: dementia and the arts | Neuroscience | The Guardian

Amnesia | Types, Symptoms, Causes, Illness & Condition

My parents have memory troubles - could it be dementia?

Dementia Symptoms: Memory Loss, Mood and Personality Changes, and Other Common Symptoms of Dementia

Memory - Forgetting | Britannica

Inhibition of Rac1-dependent forgetting alleviates memory deficits in animal models of Alzheimer's disease | SpringerLink

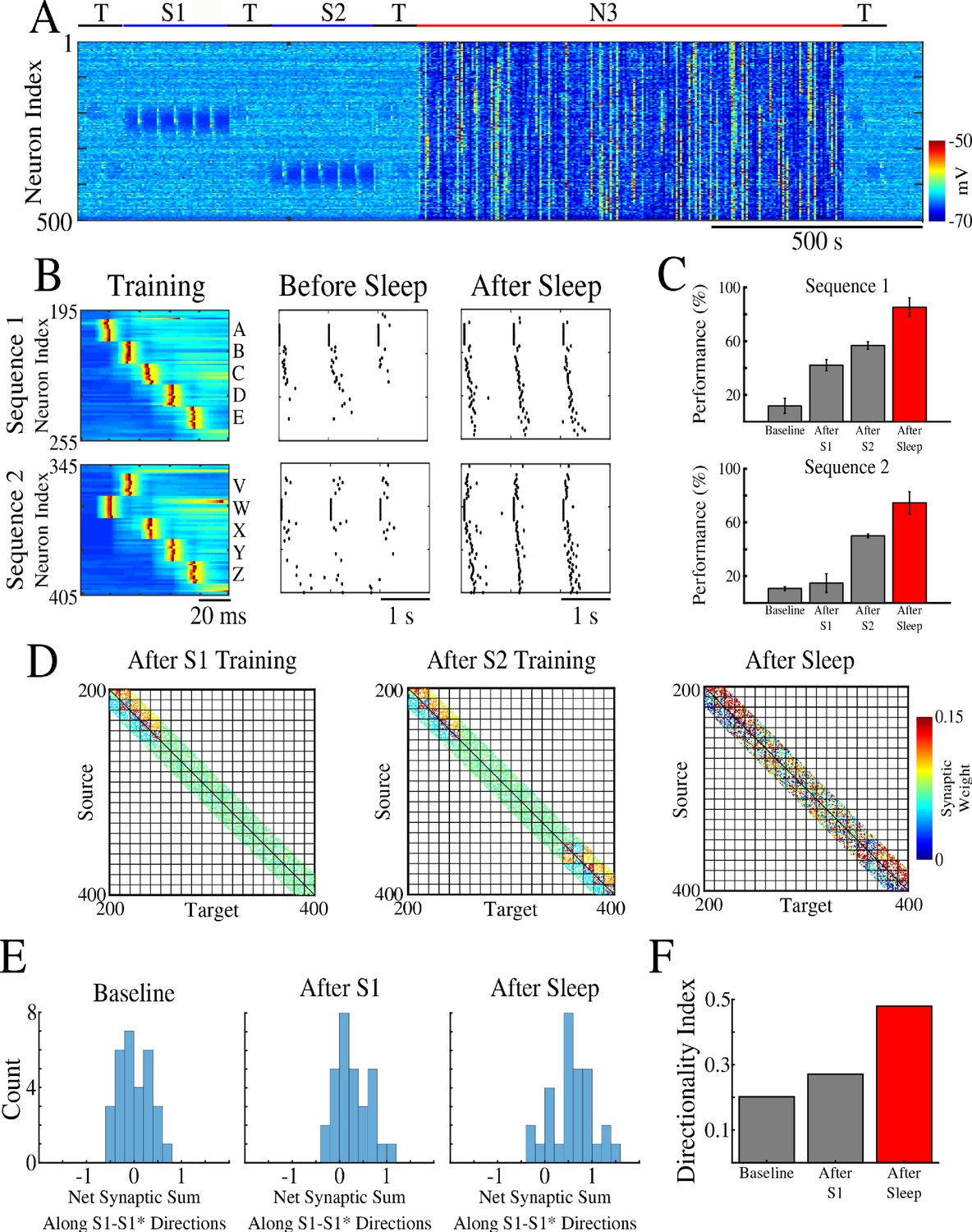

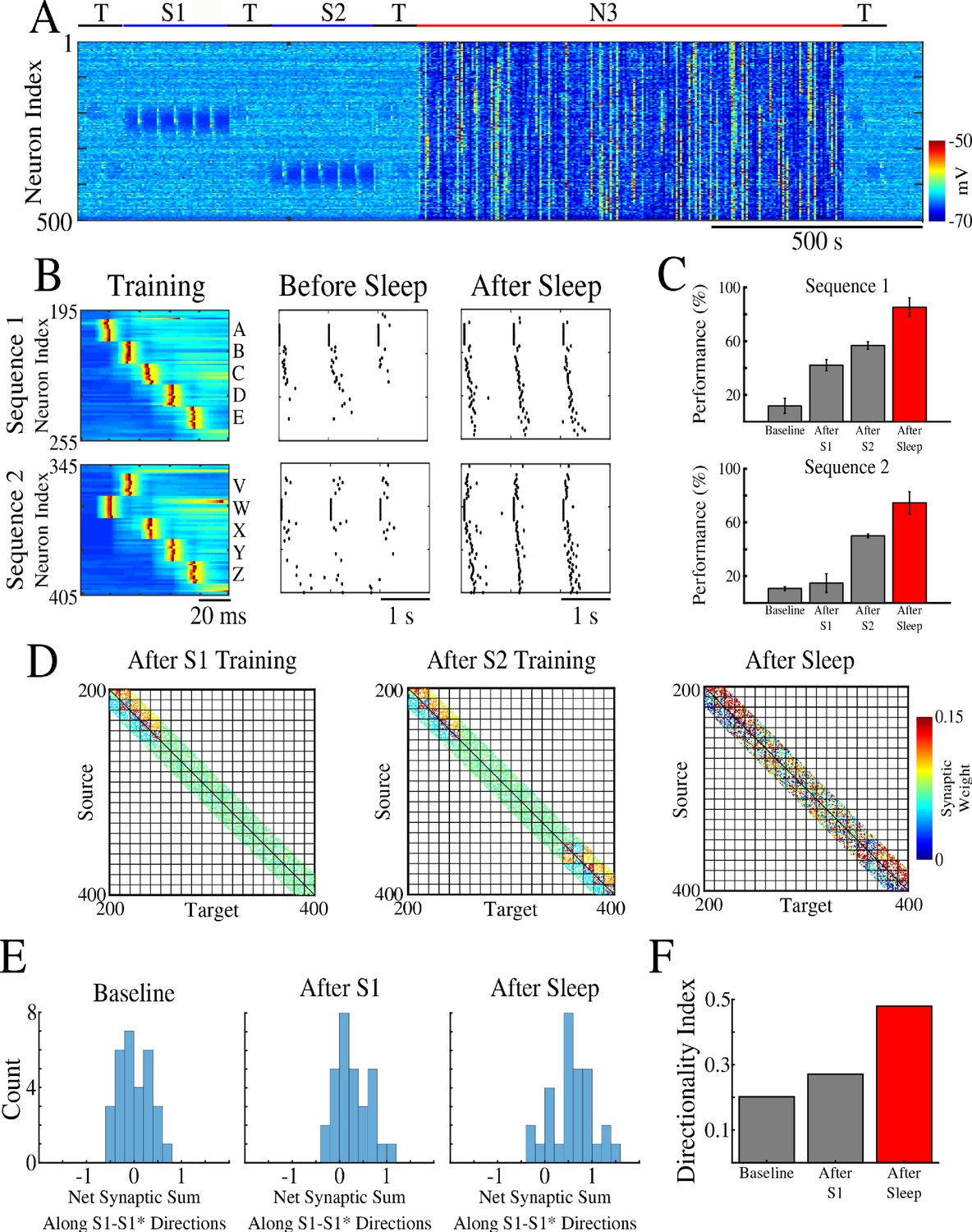

Can sleep protect memories from catastrophic forgetting? | eLife

Alcohol and Memory Loss: Connection, Research, and Treatment

Can sleep protect memories from catastrophic forgetting? | eLife

Aging and Memory: A Cognitive Approach

Why forgetting may make your mind more efficient

IGNORANCE, FORGETTING, AND FAMILY NOSTALGIA: Partition, the Nation State, and Refugees in Delhi

The effect of working memory maintenance on long-term memory | SpringerLink

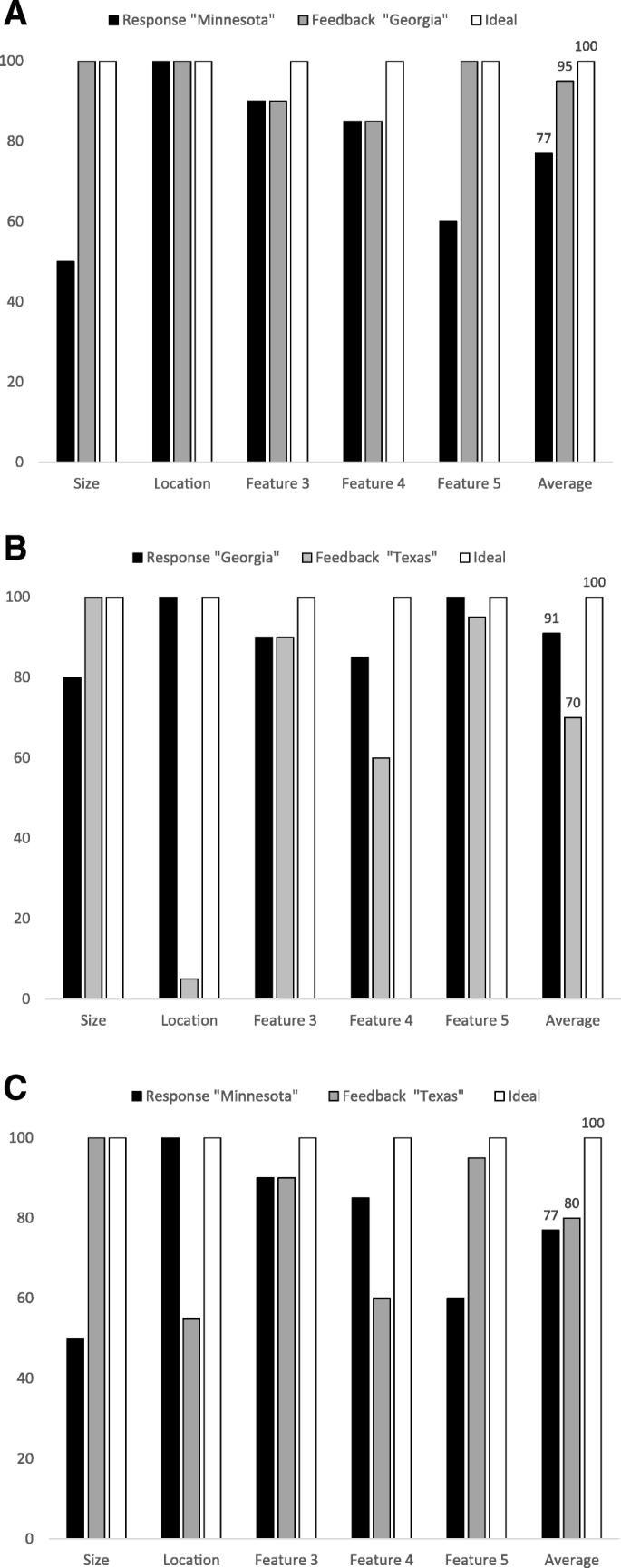

Memory and truth: correcting errors with true feedback versus overwriting correct answers with errors | Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications | Full Text

Recognition versus Recall as Measures of Television Commercial Forgetting

Microglia mediate forgetting via complement-dependent synaptic elimination | Science

Chapter 7 PSYC 2013 Flashcards | Quizlet

Chapter 7 PSYC 2013 Flashcards | Quizlet

/confabulation-definition-examples-and-treatments-4177450_FINAL-c1dd037aeb66402a9d44c5c2490467b5.png)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-592016219-58b0a7403df78cdcd8da56e6.jpg)

/do-thyroid-disorders-cause-forgetfulness-98837_V3-362c2781bfe746eb8d438a1559fe8eb9.jpg)

Posting Komentar untuk "which of the following examples indicate memory problems as a result of forgetting?"